Hey—it’s been a while…

For a variety of reasons, Erik and I decided to take the entire month of February off from writing WEH. Between busy work schedules and Erik’s international travels (I’m sure he’ll come through with some fascinating reportage soon), we needed the break. Reflecting on it, I think we may make it a regular thing—disappearing every February. There’s something about the shortest month of the year that feels like the real “end” of the year. Winter makes its last, desperate swing at collective morale, the social hangover from the holiday season finally fades, and the promise of spring brings with it a new start.

When I wasn’t at the office or the tennis courts last month, I found myself consumed by a whirlwind of media and discourse on the changing state of global politics. Everywhere I turned, there was a new think piece on geopolitics, each exploring some unprecedented shift. America’s shrinking role on the global stage is shaking things up, there are tensions over undersea internet cables, something or other is always happening in the South China Sea, and Middle Eastern sovereigns are still buying up sports teams. If nothing else, all this uncertainty and change certainly makes for a fascinating news cycle.

One of the most thought-provoking pieces I consumed during this period was a podcast by Bloomberg, featuring economists and historians from none other than Goldman Sachs. The guests’ expertise lie at the intersection of geopolitics and technology, and most of the discussion centered around China’s new AI advancements (like DeepSeek) and whether we’ve just entered a new “Sputnik moment” in the race for artificial intelligence—you know, the one that could actually cost us our jobs.

Now, this isn’t a post about geopolitics or AI, but more about an idea that caught my attention during that podcast. Casually, the host remarked on a pattern that’s emerged in the post-WWII global order. It goes something like this:

The U.S. creates a shiny new thing, often by accident or sometimes by throwing ludicrous amounts of capital at two really smart kids that went to M.I.T.

Asia refines or commercializes it, showing the world how to make the most of it.

Europe legitimizes it by introducing regulatory frameworks and offering institutional buy-in, making the product widely acceptable.

This idea is easy to follow with a few examples. For instance, the recent OpenAI breakthrough from the U.S. was followed by China’s own advancements with DeepSeek, and now Europe is stepping in with calls for AI safety regulations. The same pattern plays out in social media: the U.S. birthed Instagram, China’s TikTok took mobile social media to new heights, and Europe imposed privacy laws that hold these companies to a higher standard.

As I thought about this dynamic, I couldn’t help but see it play out in the clothes we are all wearing. And sure, it’s not like this stuff is important, but I think theory is pretty solid. Here’s a few examples:

New Balance:

A Piece of American History

New Balance has long been known as the ultimate dad sneaker—comfortable, functional, and the go-to shoe for reliable fathers who spend their weekends mowing lawns or taking care of the yard. There’s no shame in it; the brand made a great product, and it had a deep connection to the American middle class. But in the 80s and 90s, New Balance was more Tim “The Toolman” Taylor core than something we might call en vogue.

I Just Want to Be a City Boy

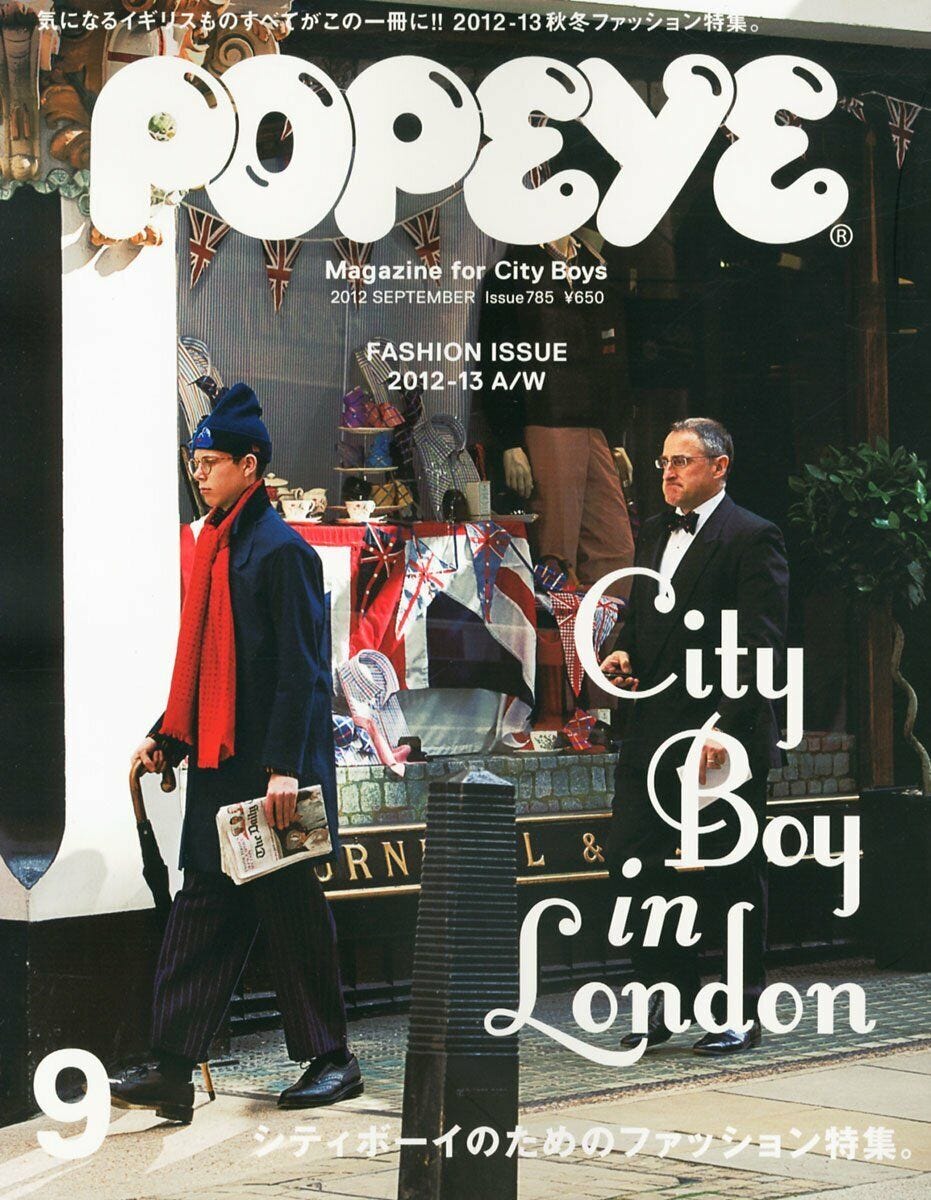

Enter Tokyo and Hong Kong. It was in these cities that the chunky, comfortable sneaker was elevated to its current status. I’m not sure if it was Popeye magazine or the general City Boy phenomenon in Tokyo and Hong Kong, but these guys deserve all the credit for showing the world how to wear a chunky and comfortable sneaker. I mean seriously, why didn’t I think of wearing some fresh NB 990s with a WTAPS hat, oversized oxford and baggy army trousers. Perhaps the white American youth of the mid-aughts was still reeling from the end of pop punk and warped tour; such a mind could not possibly have conceived what one ought to wear with a chunky tennis shoe. There’s something distinctly fresh and new about this combination that American youth at the time had no chance of cultivating.

Institutional Blessing

Finally, and as the usual stalwarts of what is acceptable in civil society, the big European fashion houses got on board. By legitimizing the look, it signaled to the world, “Hey guys, we’ve thought about it and we’ve decided it’s safe for you to wear this.”

Balenciaga’s chunky sneakers are perhaps the first example to come to mind, but we all know the large heritage brands of continental Europe all pulled from the same design language. Once Europe threw its institutional weight behind the dad sneaker trend, it no longer felt like a novelty—it became an accepted and celebrated fashion choice. At that point, wearing oversized sneakers with wide pants wasn’t just a subcultural look; it was just culture.

Denim:

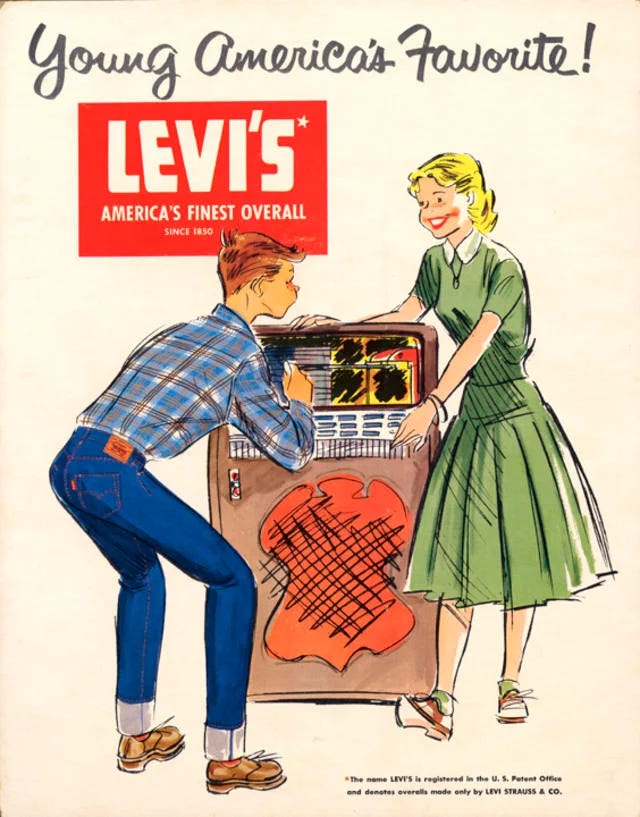

Good Ole Levi’s

Before sneakers, there was denim. Levi Strauss is the name synonymous with the creation of the iconic blue jean, which started as functional workwear but became ingrained in American culture. Call it a simple twist of fate, but I can’t get past the irony that Mr. Strauss made these jeans for his store in San Francisco; the same birthplace of many of the tech giants that prompted this entire train of thought. There’s something poetic about how denim, originally made for miners during the gold rush, became a symbol of the American working class.

Japanese Selvedge

While the U.S. certainly laid the foundation, it was Japan that took denim to the next level. With an obsessive focus on dyeing methods, stitching techniques (selvedge), and overall craftsmanship, Japan transformed denim into a high art form. It’s no surprise that this version of jeans became the pinnacle for fashion lovers everywhere, particularly those looking for a more refined, bespoke version of the workwear staple.

$1000 for Knee Designs

And now, denim has evolved into a symbol of status. No longer just a functional piece of clothing, denim is now couture. It’s a far cry from its humble beginnings, when labels like Celine convince Kendrick to wear some god awful flares for his half-time show. The workwear of miners has been transformed into a luxury item, a sign of how deeply denim has been institutionalized as a fashion statement—blessed, of course, by European haute couture houses.

[for the record, I still think one of Erik’s greatest ideas is to get Loewe knee tattoos]

Army Surplus/Chinos:

Chinos, originally made popular in the U.S. by soldiers during World War II, also follow a similar pattern. Their rise in fashion is closely linked to the Ivy League look, which was championed in the U.S. in the mid-20th century. But somewhere along the way Americans forgot about the sartorial lineage.

Japanese Revival

Japan, with its deep fascination for U.S. prep and Ivy League style, took chinos and army surplus jackets and other standard issue items and refined them to a level of cultural perfection. The book Take Ivy, which captured how U.S. college students dressed at various New England ivy league schools, became a source of inspiration for the Japanese fashion scene, which reinterpreted and elevated this look.

European Legitimacy

Now, Ivy League style and the classic chino have become staples in menswear around the world. Labels like Drake’s and other European brands blend Ivy with contemporary design, making these once-niche pieces of clothing legitimate, timeless, and universally accepted.

I don’t know. I can already see plenty of holes to poke in this pet theory. The most obvious being that it kind of lumps these countries into large stereotypical regions when there’s a lot more uniqueness on a city by city basis. But whatever, it’s just fun to think about. When I do travel around the U.S., or just live my day to day life here for that matter, it honestly surprises me that this is the birthplace of so many great ideas. As I get older though, I think I’m assigning less and less value to having a good idea and rushing to make it. There’s something more desirable about the conscientiousness it takes to refine it or contextualize it in a way that truly makes it shine.

-B.R.

This was a fun read and I agree with your theory. I went to Japan and found their interest in Americana fascinating. Even the Burger Kings there had all very American names for their burgers, literally American Classic, etc.

Personally I’ve always been a fan of the dad sneaker. New Balance 990s all the way, in particular the JJJJounds are where it’s at.

Thanks! JJJJound is the way. Love the Reebok Club Cs they did as well.